Fish screening in New Zealand: Lessons from the past, strengths, and areas for improvement

Fish screening plays a vital role in protecting aquatic ecosystems by preventing fish from entering irrigation systems and other water intake structures. New Zealand (NZ), with its diverse geography and rich aquatic life, has faced its share of challenges and achievements in the field of fish screening. In this blog post, we will explore the history of fish screening in NZ, highlighting its strengths and weaknesses, and discuss valuable lessons that can be learned for the betterment of fish screening practices.

History of screening in NZ

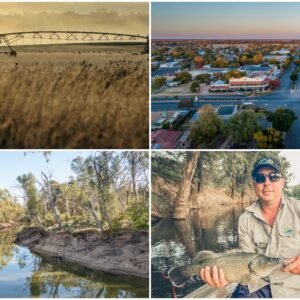

From the 1970’s on, Canterbury witnessed the installation of drum screens which were successful in limiting debris entering irrigation races but falling short in terms of effective fish exclusion. These early screens, which were perpendicular to the flow with rotating paddles, were not compliant with modern fish screening criteria. However, they laid the foundation for the evolution of fish screening practices in the country (Table 1).

In 2007, NIWA (National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research) and Environment Canterbury (ECan) collaborated to develop fish screen guidelines, drawing inspiration from international best practices, particularly those from the United States. Despite these guidelines, the adoption of more efficient mesh/mechanical screens was initially slow due to concerns about cost and sediment loads in NZ rivers.

Bossman Screen

However, in recent years, there has been a shift towards mesh/mechanical screens in NZ, driven by factors such as the establishment of the Fish Screen Working Group (FSWG), pushback on alternative screening methods like rock bunds, and a focus on compliance by regulatory bodies like ECan. Research initiatives and trials have also been conducted to study native fish behaviour and improve fish screening practices.

A study from 2019-2023 has just been completed which including lab testing and live fish screen and testing review of the 2007 guidelines. The final report has just been released in the last week titled Toward national guidance for fish screen facilities to ensure safe passage for freshwater fishes.

Strengths

Despite the challenges, NZ has demonstrated commendable strengths in its fish screening efforts.

- Development of guidelines. NZ’s development of fish screen guidelines based on international best practices, particularly from the US, showcases a commitment to improving fish exclusion measures.

- Shift towards efficient screens. NZ’s willingness to explore and adopt mesh/mechanical screens, despite initial concerns, indicates a proactive approach to implementing more effective technologies for fish exclusion.

- Active auditing and compliance. ECan’s proactive auditing of fish screens and emphasis on compliance assessment highlight the commitment to ensuring adherence to regulations and driving improvements in screening practices.

- Collaborative efforts. The establishment of the FSWG, bringing together industry stakeholders, regulators, and manufacturers, demonstrates NZ’s commitment to collaborative problem-solving and finding effective solutions.

- Focus on research and good practices. NZ’s emphasis on research, lab trials, site studies, and the development of tools and documents to explore good fish screening practices is a testament to their dedication to advancing fish exclusion techniques.

- Recognition of skills and experience gaps. The identification of gaps in regulatory and design expertise in fish screening and the efforts to address these gaps through training workshops indicate a proactive approach to building the necessary skills and knowledge within the industry.

Infiltration Gallery Central Plains Water – In construction.

Lessons learned

While NZ has made significant strides in fish screening, several areas for improvement and valuable lessons have emerged.

- Historical screening measures. Most of the early approach to fish screening used drum screens which if designed correctly can be effective fish screens but almost all were installed without the knowledge of what was required. This highlighted the need for a better understanding of what is required for an effective fish screen.

- Separation of consenting and compliance. The separation of consenting and compliance processes has created uncertainties and compliance issues, emphasizing the need for clearer regulations and alignment between these stages.

- Limited impact of the FSWG. The lack of regulatory powers and dependence on regulatory body agreements limited the effectiveness of the FSWG, emphasizing the importance of empowered decision-making bodies.

- Gaps in skills and experience. Identifying gaps in regulatory and design expertise underscores the need for continuous professional development and knowledge sharing to enhance fish screening practices.

Conclusion

The history of fish screening in NZ showcases the country’s commitment to improving fish exclusion measures and protecting aquatic ecosystems. By developing guidelines, embracing research, and fostering collaboration, NZ has laid a solid foundation for the advancement of fish screening practices. While challenges such as historical screening measures and skills gaps persist, these weaknesses provide valuable lessons for further improvement. By addressing these weaknesses and building upon their strengths, NZ can continue to lead in the development of effective fish screening methods, ensuring the long-term sustainability of its aquatic ecosystems.

| Period | Description |

| 1970s – 1990s | Many smaller intakes in NZ, particularly in Canterbury, had drum screens installed, which were effective debris screens with limited fish exclusion capability. These screens are not compliant with modern fish screen criteria and require complete reconstruction. |

| 2007 | NIWA Canterbury fish screen guidelines were established based on international practices, particularly those from the US. |

| 2007 – 2017 | Mesh/mechanical screens were not commonly used in NZ due to concerns about their cost and their ability to handle high sediment and debris loads in NZ rivers. Rock bunds and infiltration galleries were preferred over mesh/mechanical screens. |

| 2017 | There was a shift in thinking towards mesh/mechanical screens, driven by factors such as the focus of Environment Canterbury (ECan), the establishment of the Fish Screen Working Group (FSWG), and pushback on rock bunds. |

| 2019-2023 | The Ministry of Primary Industries and Irrigation NZ initiated a project to study good practice with fish screens. The project included lab and flume trials, as well as an assessment of the current state of fish screens across different regional councils in NZ. |

| Current | ECan has been auditing fish screens and requiring consent holders to construct new fish screens on consent renewal for over 95% of cases. Many other regional councils are starting to consider fish screen requirements and many use the 2007 Guidelines and likely they will reference the 2023 report for future consenting and compliance of fish screens in their regions. |

| Current | Despite active efforts by ECan and the FSWG, there are challenges in progressing fish screen work in Canterbury due to a number of issues, including some inconsistencies and gaps in theguidelines , separation of consenting and compliance processes, and gaps in skills and experience. Other regions have significantly less surface water intakes but a number are including consent requirements for fish screens. |

| Current | The FSWG is undergoing a review process for its future involvement and potential advisory role for ECan and other councils. |

| Current | The 2023 report Toward national guidance for fish screen facilities to ensure safe passage for freshwater fishes is likely to be adopted as basis of good practice in the design of fish screen facilities across all of NZ as it has updated the 2007 Guidelines written specifically for Canterbury. |

Table 1. Major developments in the history of modern fish-protection screening in NZ.